In the last episode #17, we saw how optimization problems can be turned into physics problems. By carefully designing a Hamiltonian, we let a quantum system relax into its ground state, which encodes the optimal solution we were looking for. This idea is known as adiabatic quantum computation.

There is a big secret I quietly swept under the rug last time. Adiabatic quantum computing is universal. This means it is computationally equivalent to the circuit based model of quantum computing, the one used by Google and IBM, and also to measurement based quantum computing (MBQC), pursued by companies like PsiQuantum and Xanadu.

Universal is a strong word. It means that all these are built to solve various types of problems. Just like modern laptops, they are general purpose machines.

But general purpose is not always what we want.

Think about the computers inside ATM machines or supermarket checkout counters. They are not designed to browse the web or edit photos and watch videos. They do one thing and they do it well. They handle payments and nothing more.

This raises a natural question.

Do quantum computers also have specialized versions, machines built to excel at a specific task rather than everything at once?

As you might have guessed, the answer is yes.

Let me introduce you to the close cousin of adiabatic quantum computing, one that is even more inspired by real physical processes. It is called quantum annealing which is used for more specific optimization problems (like the packet delivery problem we discussed in episode #1).

To understand it, we first need to take a short detour into metallurgy, cooking, and everyday frustration.

Annealing in the Real World

Annealing is not a quantum idea. It is an old and very physical one comes from studying of metals under heat.

Consider metalworking. When you heat a piece of metal until it glows and then let it cool slowly, the atoms inside have time to rearrange themselves into a more ordered, lower energy structure. The metal becomes stronger and less brittle.

If you cool it too quickly, the atoms freeze in awkward positions. The result is stress, defects, and weakness.

Cooking provides another analogy. Imagine making caramel. If you heat sugar gently and allow it to settle, you get a smooth, glossy syrup. If you rush it, you end up with burnt clumps and bitterness. The pattern is always the same.

Heat allows distant exploration. Slow cooling allows optimization.

This idea exists in our normal computing as well, under the name simulated annealing.

Simulated Annealing

Imagine trying to find the lowest point in a foggy mountain landscape. You cannot see the whole terrain. You can only sense whether the ground slopes up or down at your current position.

A naive strategy is to always walk downhill. While this feels sensible, it often fails. You may quickly reach the bottom of a small valley and stop there, even though a much deeper valley exists elsewhere. Once stuck, every direction looks worse (see image below).

Simulated annealing deliberately avoids this trap.

Early in the algorithm, random steps are allowed, including steps that go uphill and temporarily worsen the solution. This randomness plays the role of heat in metallurgy. When the temperature is high, the system explores freely and can escape shallow valleys.

As time passes, the temperature is slowly lowered. Random uphill moves become rarer. The algorithm becomes more cautious, favoring downhill steps that improve the solution. Eventually, at low temperature, the system settles into a stable minimum. The key idea is simple but powerful.

You accept disorder early to achieve order later.

By carefully controlling how randomness fades away, simulated annealing balances exploration and stability, increasing the chance of finding a truly good solution rather than the first acceptable one.

From Classical to Quantum

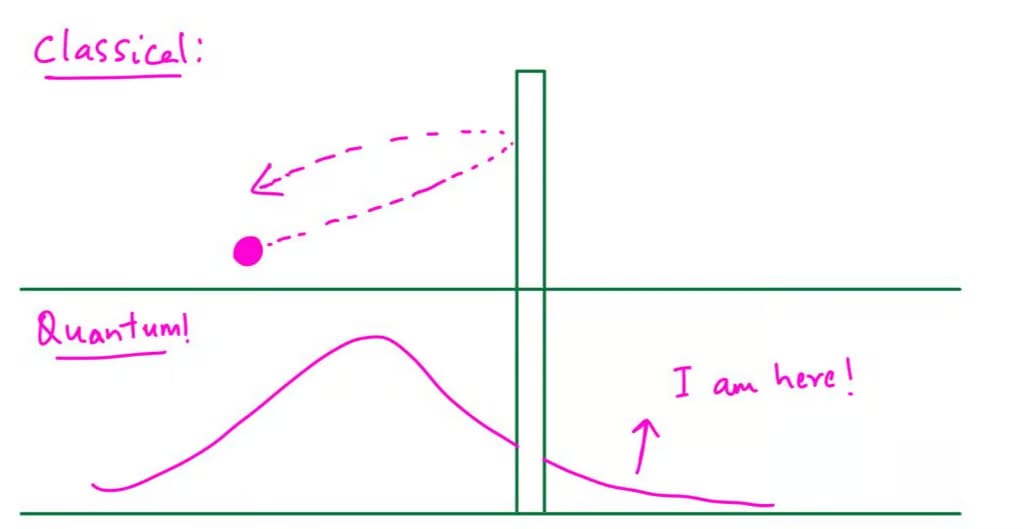

Quantum annealing builds directly on this picture but replaces classical randomness with quantum mechanics. Quantum systems have a remarkable advantage here. They can tunnel.

As we discussed in episode #5, in quantum mechanics, particles are not limited to classical motion. They can tunnel through barriers that they do not have enough energy to climb over. Just like how harry potter and others could go to the 93/4 platform!

In our landscape picture, this means something remarkable.

A quantum system does not always need to climb over hills to find a deeper valley. It can sometimes pass straight through them. This is the key intuition behind quantum annealing.

Early in the computation, the system is dominated by quantum fluctuations. These fluctuations allow the system to explore many configurations at once and tunnel through barriers between them. As time goes on, these quantum effects are gradually reduced. The system becomes more classical and settles into a low energy configuration.

In other words, we start with a lot of quantum motion and end with quiet relaxation.

How Quantum Annealing is Implemented?

Conceptually, quantum annealing looks very similar to adiabatic quantum computation as discussed in the last episode (read here).

We again define a problem Hamiltonian whose ground state encodes the solution to our optimization problem. We again start from an initial Hamiltonian that is easy to prepare.

The crucial difference lies in emphasis and intention. In adiabatic quantum computation, the goal is to remain in the ground state at all times. Transitions to excited states are considered errors.

In quantum annealing, controlled excitations are possible and useful. The system is allowed to explore excited states early on, assisted by quantum fluctuations. As these fluctuations are slowly turned off, the system settles into a low energy state, ideally the global minimum.

You can think of it as the first shot in billiards or carrom. It is energetic and somewhat random, scattering all the balls across the table, but rest of the game you play very slowly carefully guiding the balls to the pockets.

Final Thoughts

Quantum annealing builds on the same physical intuition as adiabatic quantum computation, but with a narrower focus. It is primarily suited for optimization problems, and unlike gate based quantum computing, noise and imperfections in the system are not necessarily a drawback. In fact, given how noisy today’s quantum hardware still is, such specialized machines are often seen as more realistic near term devices than fully universal quantum computers.