Before you laugh at the title, yes, I really do mean that Despacito. The song. The one that crossed eight billion views. If you do not know it, feel free to listen to it here and know what the word means!

In the last episode (read here), we discussed two different but equivalent models of quantum computing: the circuit or gate model and the measurement based model, often called MBQC. Naturally, a question arises.

Are these the only ways to do quantum computing?

The answer is no. And today we explore a third model, one that is much closer to physics itself. To get there, we need to understand two key ideas first.

1. Solving a Problem by Reduction

Sometimes, instead of solving a problem directly we turn it into a different problem that is easier to deal with.

Imagine three friends: A, B, and C. A owes money to B, and B owes the same amount to C. One way to settle this is for A to pay B, and then B pays C. But clearly, A could just pay C directly. Same outcome, fewer steps.

This idea is called reduction. You reduce a problem to a simpler or more convenient one without changing the final answer.

Here is another everyday example.

Consider vitamin D. Your goal is to maintain healthy vitamin D levels. Going outside every morning is a solution. However, we can reduce this problem to something else altogether like taking a supplement pill. By choosing a supplement, you have reduced a complex routine involving time, weather, and motivation to a simple daily action. The goal stays the same. The method changes.

The key lesson is this. Sometimes the best way of solving a problem is not solving it, but translating it into a form that is easier to work with.

Keep this idea in mind. We will need it very soon.

2. Hamiltonian: The Energy Rulebook

Energy plays a central role in physics, and quantum mechanics is no exception. In quantum mechanics, every system is described by a state, and each state has an associated energy as discussed in the episode #5. Among all possible states, there is one with the lowest energy. This is called the ground state (image from episode #5).

The object or function that tells us the energy of each possible state is called the Hamiltonian. You can think of it as the energy rulebook of the system.

If you change something about the system, for example external electric fields, magnetic fields, or interactions between particles, the Hamiltonian changes. When the Hamiltonian changes, the energy landscape changes, and so does the ground state.

Why do physicists care so much about ground states?

Because systems naturally prefer to sit there. If you leave a system alone and let it relax, it tries to minimize its energy.

This idea will soon connect beautifully with optimization problems.

Back to Quantum Computing

Let us take a classic optimization problem, like the traveling salesman problem. You want to deliver parcels to many locations while minimizing the total distance traveled as discussed in the very first episode of the blog, read here.

The brute force solution is to try every possible route and pick the shortest one. Unfortunately, this becomes impossible very quickly as the number of locations grows. Even with powerful computers, the problem explodes.

So we ask a familiar question. Can we reduce this problem to something else?

Yes, and this is where the magic happens. In optimization, we try to minimize a cost function. For the delivery problem, the cost could be the total distance traveled.

In physics, systems try to minimize energy.

So here is the crazy but brilliant idea. Construct a quantum system whose Hamiltonian is designed so that its ground state energy is exactly the minimum value of the cost function we care about.

If we manage to do this, then finding the optimal delivery route is equivalent to finding the ground state of a quantum system.

Read that again. Slowly.

The problem of choosing the best route for delivering parcels becomes the problem of finding the lowest energy of a quantum system.

This mapping was first formalized in early work on adiabatic quantum computation, notably by Farhi and collaborators in the early 2000s (read original article here). Companies like D-Wave use this approach to build a quantum computer.

How Does This Actually Work?

There is a catch. The Hamiltonian that encodes the solution to our problem is usually very complicated. Preparing its ground state directly in that configuration is extremely difficult.

So we do something clever. We start with a Hamiltonian H₀ whose ground state is easy to prepare. We initialize the quantum system in that ground state, with energy E₀.

Then, very slowly, we change the Hamiltonian from H₀ to the final Hamiltonian Hf, the one that encodes our cost function.

If we do this slowly enough, the system stays in its ground state throughout the evolution. By the end, the system sits in the ground state of Hf. The corresponding energy Ef is the minimum value of our cost function.

That is our answer.

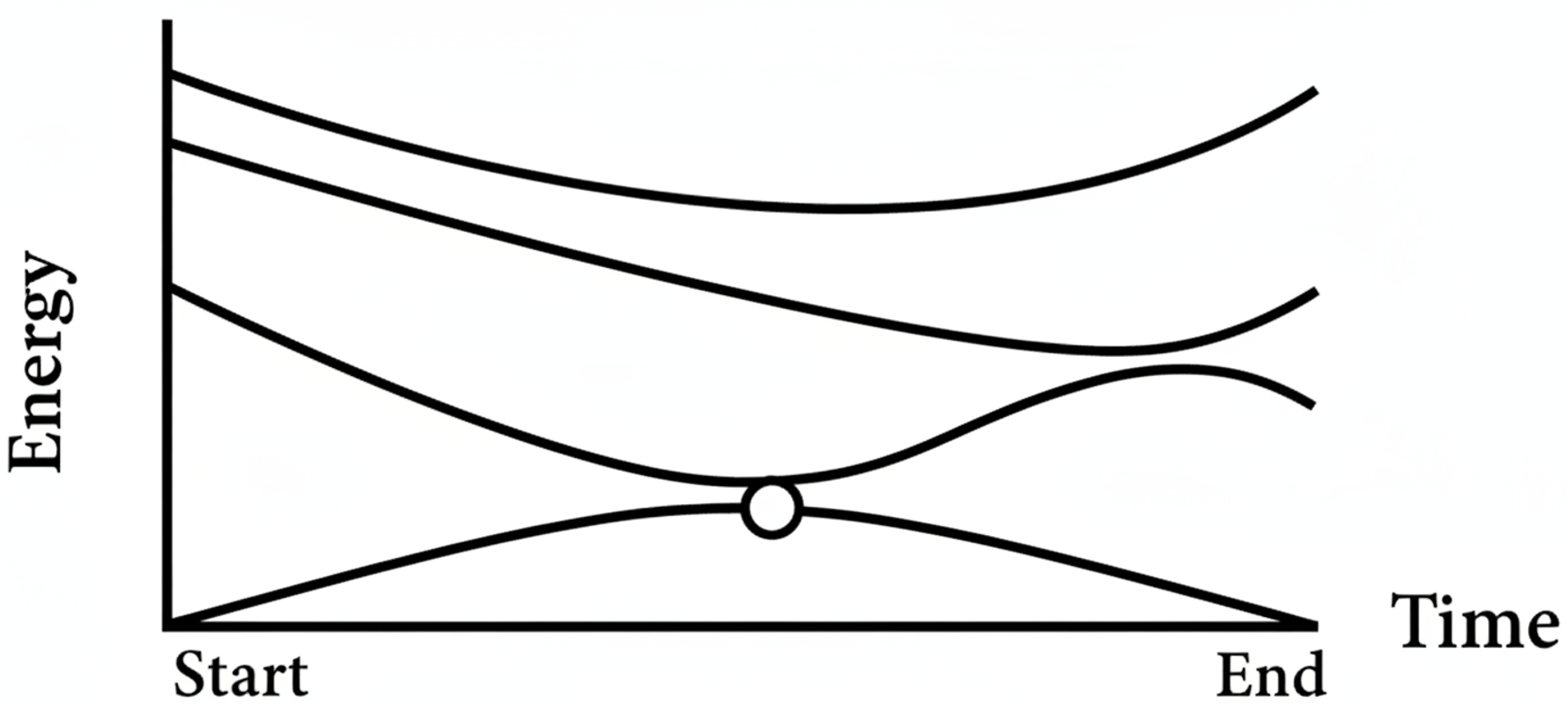

The entire computation is encoded in a slow, continuous change of the system’s energy rulebook as shown in figure below.

Why Slowly Matters

This is where physics steps in with a powerful guarantee.

The adiabatic theorem tells us that if a quantum system is evolved slowly enough, it remains in its instantaneous ground state. No unwanted jumps. No surprises.

If we rush the process, things go wrong. It may jump to higher energy states instead of staying in the ground state (see the image below). Those states correspond to suboptimal solutions.

So the rule is simple. Go slowly, and the system guides you to the solution.

Adiabatic, in physics language, literally means slow. Des… pa… ci…to.

Final Thoughts

Adiabatic quantum computing flips our usual idea of computation on its head. Instead of issuing precise instructions, we design a physical system and let it relax. The computer does not calculate the answer step by step. It becomes the answer by settling into its lowest energy state.

Even more strangely, speed is no longer a virtue. Rushing the system ruins the computation. Slowness is what protects the solution. The harder the problem, the more carefully we must go.

It is computation by physics doing what physics likes to do anyway, namely minimizing energy.