This is a special episode where we take a short detour from our Quantum Technology Series (check it out here) and step into the Nobel Prize Series. Here’s my take on this year’s physics prize — and as always, take it with a pinch of salt!

Official statement from the Nobel Committee:

The Nobel Prize in Physics 2025 was awarded jointly to John Clarke, Michel H. Devoret and John M. Martinis "for the discovery of macroscopic quantum mechanical tunnelling and energy quantisation in an electric circuit"

There are several important ideas packed in the above statement — macroscopic, quantum, quantum tunnelling, energy quantization, and electric circuits. Let’s take a moment to understand each of these concepts in detail before we connect them all together.

What is Quantum?

There are several key differences between classical and quantum physics, but I’ll focus on the one that matters here. The word quantum means discrete. Some things in nature are inherently discrete — they can be counted in whole numbers, such as steps, books, or people. You can have 7 or 8 children, but not 7.2. Other quantities, however, are continuous. For example, you can have 7.2 liters of milk.

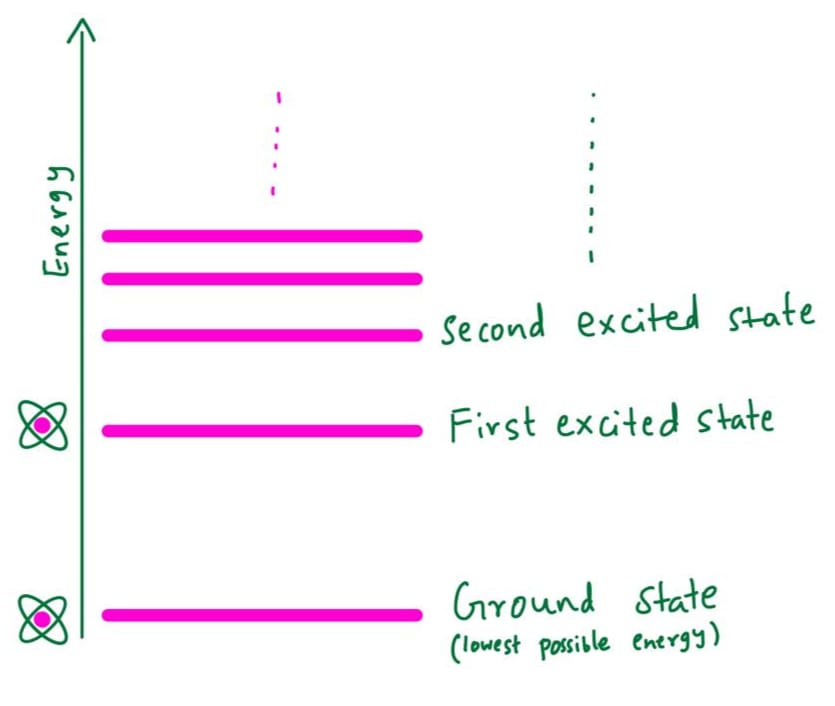

In classical physics, energy was thought to be continuous — it could take any value. Quantum mechanics, on the other hand, tells us that energy is not continuous but comes in tiny, discrete packets called quanta. That’s where the term quantum comes from. So, when we look at an atom and ask what energies its electrons can have, we find that they occupy specific, discrete energy levels — forming what is known as an energy spectrum. Having energy restricted to discrete levels is called the quantization of energy. The figure below illustrates the atom's energy levels.

What is Quantum Tunnelling?

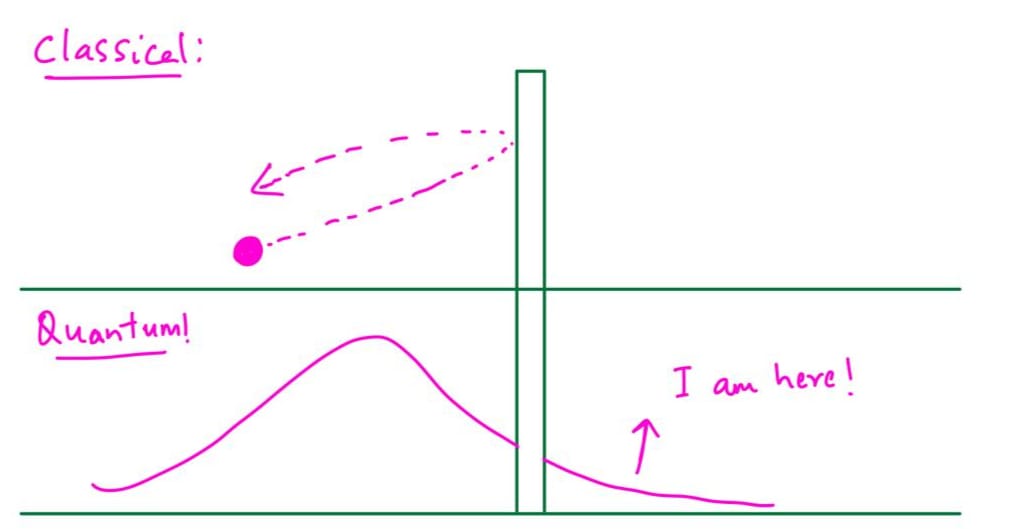

Quantum tunnelling is one of the most counterintuitive phenomena in physics. Imagine throwing a ball at a wall, and instead of bouncing back, it passes right through! That’s what quantum tunneling means. Of course, this never happens in everyday life, but if you shrink the ball down to an extremely small size and make the wall very thin, it becomes possible. In the quantum world, there’s a non-zero probability that a particle can be found on the other side of a barrier, even though it doesn’t have enough energy to climb over it. The barrier is not literally punched through. Instead the particle’s wave like description extends into and beyond the barrier, and there is a chance to detect it on the other side.

This is the principle behind the working of STM microscopes and SSD memory drives.

What is macroscopic?

Macroscopic means large, while microscopic means small. Quantum effects usually occur at the microscopic level — they are typically observed only on very small scales, such as with atoms or subatomic particles.

Observing macroscoping quantum phenomena is extremely interesting fundamentally and for practical applications. The famous thought experiment known as Schrödinger’s cat is one such example, where a cat can be considered both dead and alive at the same time — a concept we’ll explore in another episode.

The discovery

Now let’s connect the dots to understand the discovery. Scientists had conjectured that it might be possible to observe quantum tunneling effects in superconducting circuits, and this is exactly what they observed. Additonally they also observed the energy quantization. Let us look at them in detail:

1. Macroscopic Quantum Tunneling in Superconducting Circuits

Imagine a small electric circuit or wire carrying current. Normally, this current comes from the flow of electrons, but their motion is hindered by collisions with other electrons and atoms in the material — this is what we call resistance. However, when you cool the metal to extremely low temperatures, it becomes a superconductor, meaning the electrons can move without any resistance at all.

Now, suppose we cut the wire and leave a tiny gap between the two ends, filling that gap with an insulating material. Under normal circumstances, the current would stop — electrons cannot jump across the insulating barrier, and we would expect no voltage. At first, that’s exactly what was observed. But after a while, scientists began to detect a voltage and a flow of current across the gap.

How could that be possible? The answer lies in quantum tunnelling. Instead of just one or two electrons crossing the gap, many electrons tunnelled through simultaneously. This collective behaviour is known as macroscopic quantum tunnelling — a quantum phenomenon that occurs on a large, visible scale.

You can think of it like this: imagine water flowing through a pipe. When the temperature drops and the water freezes, it turns into a solid block of ice. The individual water molecules, which once moved independently, now act as one large, coherent mass. Similarly, in a superconducting circuit, the electrons behave as a single, unified quantum entity.

That is the macroscopic quantum tunnelling effect — a truly remarkable example of quantum behaviour visible at a scale we can measure.

2. Electric Circuit Absorbing Energy in Discrete Levels!

If a system behaves quantum mechanically, its energy can take on only discrete levels — specific values rather than a continuous range. To observe this, scientists sent short microwave pulses (the same kind of waves that heat your food) into the superconducting circuit and measured how it responded. What they found was remarkable: the circuit absorbed and emitted energy only at certain fixed amounts, just like an atom does. Because of this discrete energy structure, such a superconducting circuit is often called an “artificial atom.”

Conclusion

Fundamentally, what we’re saying is that each tiny superconducting circuit behaves like an atom. It has distinct energy levels, which can represent the 0 and 1 states needed for computation. Because these are circuits, we can use modern fabrication techniques to place many of them on a single chip and build up larger quantum computers.

There’s a clear advantage and a drawback here. The advantage is flexibility — since these are man-made circuits, we can design and arrange them however we like, and each one still behaves like an atom. This gives us enormous control and design freedom.

The drawback, is that real atoms of the same element — say, every oxygen atom in the universe — are identical. Artificial atoms, on the other hand, are built by us, and even the tiniest imperfections in fabrication can make them slightly different from one another. This variability introduces challenges.

Since the circuit has many energy levels, just like an atom, how can we confine it to only the 0 and 1 states? And what happens if it climbs to higher energy levels? That, of course, is a story for another episode — stay tuned!

Post Script:

Thank you my readers and Sanchar Sharma for a nice discussion! If you enjoyed the article, please do share it! I’d really appreciate your feedback to help make the content better as we go forward. Drop an email: [email protected]