In the last few episodes we explored the basics of quantum mechanics (check here), now let us switch gears and explore some interesting applications of quantum technologies!

If I ask you whether simulating something is easier than actually doing it, you might say: “Of course simulating is easier!” And nowadays, you’d be right—at least most of the time.

But if you had asked the same question back in the 80s or 90s, many engineers would have confidently told you that crashing two real cars for a movie scene was cheaper and simpler than simulating a crash on a computer. Today it’s the other way around: we simulate everything—buildings, fluid flow, pilot trainings, movies, video games, you name it.

In science and engineering, simulation is usually faster, safer, cheaper, and often more reliable than running the real experiment. But here’s the twist of today’s story:

There are experiments that are much easier to build in real life than to simulate—even on the world’s fastest supercomputers.

And to understand why, we’re going to start with something unexpectedly delightful:

pinball.

Pinball: A surprisingly good lesson in unpredictability

Have you ever played pinball? If not, treat yourself sometime—it's wonderfully chaotic.

A pinball machine is basically a metal ball bouncing through a dense forest of bumpers, rails, gates, and flashing lights. Every time the ball hits something, you get points. You try to keep it from falling out by flipping it upward again and again. Watch it here.

From the outside, pinball looks random. But if you’re an expert player, it feels like you have some control: you know roughly how the ball will behave after hitting certain parts of the machine.

So here’s a question:

Can we predict the exact path of the pinball as it bounces around?

Not really. The ball is constantly nudged by tiny imperfections: the angle of a bumper, the force of your launch, vibrations in the machine, even dust on the surface. A tiny difference early on leads to a completely different path later—a classic case of chaotic dynamics.

A simpler analogy: a maze with many entrances and exits

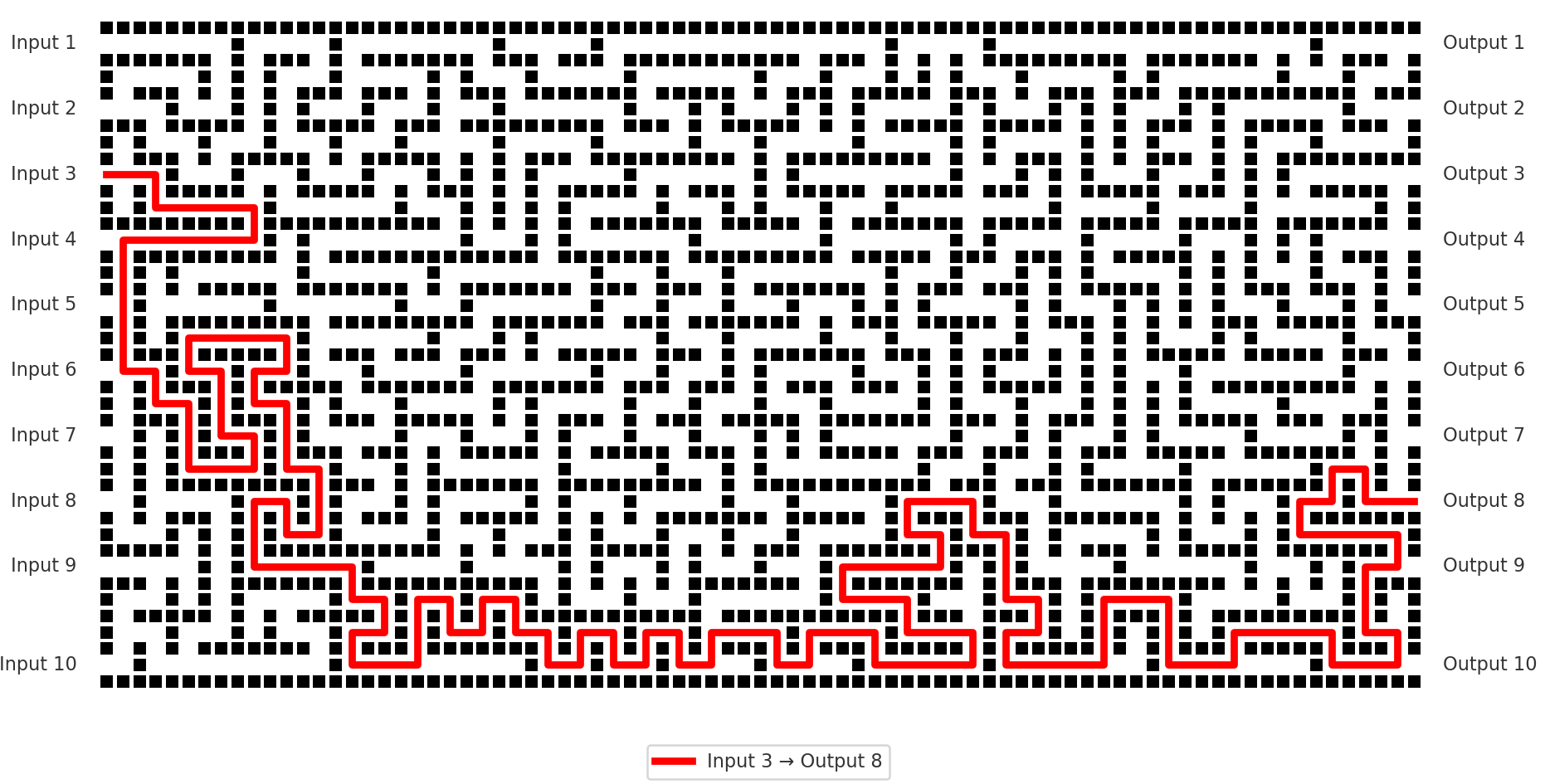

Let’s simplify further. Imagine a maze with 10 entrances and 10 exits. If you send one ball in through entrance #3, it might come out through exit #8. If you send 1,000 balls, their exits will be spread out: maybe 200 leave from exit #3, maybe 90 from exit #9, and so on. The figure below illustrates such a maze with one example path.

If you send evenly spaced particles into every entrance—10 particles per entrance—could you predict on average how many will come out of each exit?

You might say: “Why should I care?” Fair question. But stick with it—this turns out to be a prototype of something very important in quantum physics.

Now make it quantum

Instead of metal balls, imagine sending photons—particles of light—into those entrances. Between each entrance and exit there’s a whole network of beam splitters, which we talked about in earlier post (check here).

At each beam splitter, a photon faces a quantum “choice”:

go straight

or turn

If you repeat the experiment many times, you get a distribution: a pattern telling you what percentage of photons exit each output.

This task—predicting the distribution of where photons come out—is known as boson sampling.

So how do we find this distribution?

We have two options:

Simulate the whole setup on a computer, tracking all possible paths, interference patterns, and quantum correlations.

Build the optical experiment, shine light into it, and simply measure what comes out.

Here’s the punchline:

Simulating this on a computer is insanely hard— but building a boson sampler is surprisingly easy.

Even our best classical supercomputers struggle badly with realistic boson sampling setups. The number of possible quantum paths grows astronomically fast. Meanwhile, building the actual optical circuit is comparatively straightforward: mirrors, phase shifters, beam splitters, and single photons.

This mismatch is what people call quantum advantage.

What quantum advantage actually means

The term quantum advantage refers to a situation where:

A quantum device can solve a problem that is prohibitively difficult for classical computers to simulate.

In boson sampling, the quantum machine (the optical setup) naturally performs the experiment. A classical computer, on the other hand, has to track unbelievable amounts of quantum interference, and collapses under the complexity.

But don’t confuse quantum advantage with two things:

Quantum usefulness

Just because something shows quantum advantage doesn’t mean it’s immediately practical or useful.Universal quantum computing

A boson sampler is not a full quantum computer.

It can’t run algorithms or solve arbitrary problems—its only job is sampling photons through a fixed network.

Still, the fact that there exists any physical system that is easier to run than to simulate is fascinating—and encouraging.

Why this matters

Think about it: many real-world problems are tough in both directions—

hard to do in real life and hard to simulate.

If quantum machines can make progress in one direction or the other, either by simulating the physics or by performing the task physically, that’s immediately exciting.

And here’s where things get interesting from an industry perspective. Many quantum photonics companies are now racing to build larger, faster, and more stable boson-sampling devices. Some groups push the hardware forward to demonstrate stronger forms of quantum advantage; others explore new use cases, such as using these devices as components in future photonic quantum computers. This race has attracted serious investment, because even a very specialized quantum device that outperforms classical supercomputers signals something bigger: an industry willing to bet billions on photonic quantum technologies.

Boson sampling is just the beginning.

A tiny tip of a very large, very quantum iceberg.

More on that in the next episode. Stay tuned.

Bonus Video:

If you want to visualize how such a maze would work, check out the video below. Although the video was created to illustrate a different phenomenon, the mechanism is the same! Tiny balls drop and bounce through a complex network of pegs, and over many runs you see a pattern emerge — similar to how photons would spread across outputs in a boson-sampling experiment.

Some administrative details:

Some of you have mentioned issues with emails not displaying correctly or figures not loading. If that happens, you can always click “Read online” in the top-right corner of the email to view the post in your browser. You can also visit the homepage https://qubit-and-neuron.beehiiv.com/ at anytime to see the latest updates.

Thank you all for your feedback and for letting me know about these issues. Please contact at: [email protected]