In the last episode we discussed that the position and momentum of electron may not even be defined (read here). Most importantly, watch this one minute video here how electron behave when we observe! Today we talk about even more mysterious idea but before we talk about quantum cats, let us understand three ideas. Each is simple on its own, but when combined they give us a natural way to see why these strange things appears in quantum mechanics.

Idea 1: Motion is relative

Let me begin with a familiar question. Does the sun really rise in the east? It seems obvious. We watch it every morning. Yet the moment you think carefully, the picture changes. The sun rising in the east is not a universal fact. It is a fact relative to us. If you stood on a planet that rotated in the opposite direction, you would say the sun rises in the west. If you floated in deep space with no ground beneath your feet, the entire question would lose meaning. Rise relative to what?

This is the first lesson. Motion is always relative. A train moves relative to the platform. The platform moves relative to Earth. Earth spins relative to the sun. The sun orbits the center of the galaxy. There is no absolute motion. Asking whether something is moving without an observer who supplies a frame of reference has no meaning. The question itself only becomes defined when an observer enters the scene.

Idea 2: Reality is not the same as a mathematical model

From here we arrive at a second lesson that modern physics depends on. The world is one thing and the mathematical models we use to describe it are another.

When we study Earth’s motion around the sun, we treat Earth as a point. We ignore oceans, mountains, clouds and rotation. When we model a car driving down the road, we ignore the spinning pistons, rotating wheels and all the internal machinery. This is not because Earth or a car are points. It is because the model answers a specific question. If the only question is how Earth orbits, then treating it as a point works well. The model is useful, but it is not the full truth.

This distinction matters deeply in quantum mechanics. The mathematics describes the system in a particular way, but that does not mean every element of the model corresponds to a tangible object in reality.

Idea 3: Linearity and superposition in mathematics

Now we turn to the idea of superposition, which begins with something very simple. Linearity.

A system is linear when adding solutions gives a new solution. Waves give the most familiar examples. If one musical note vibrates in the air and another note is added, the combined sound is still a valid solution of the same wave equation. Water waves cross each other and continue on their way. Light shows the same behaviour under many conditions. In each case, the waves simply add. This is superposition.

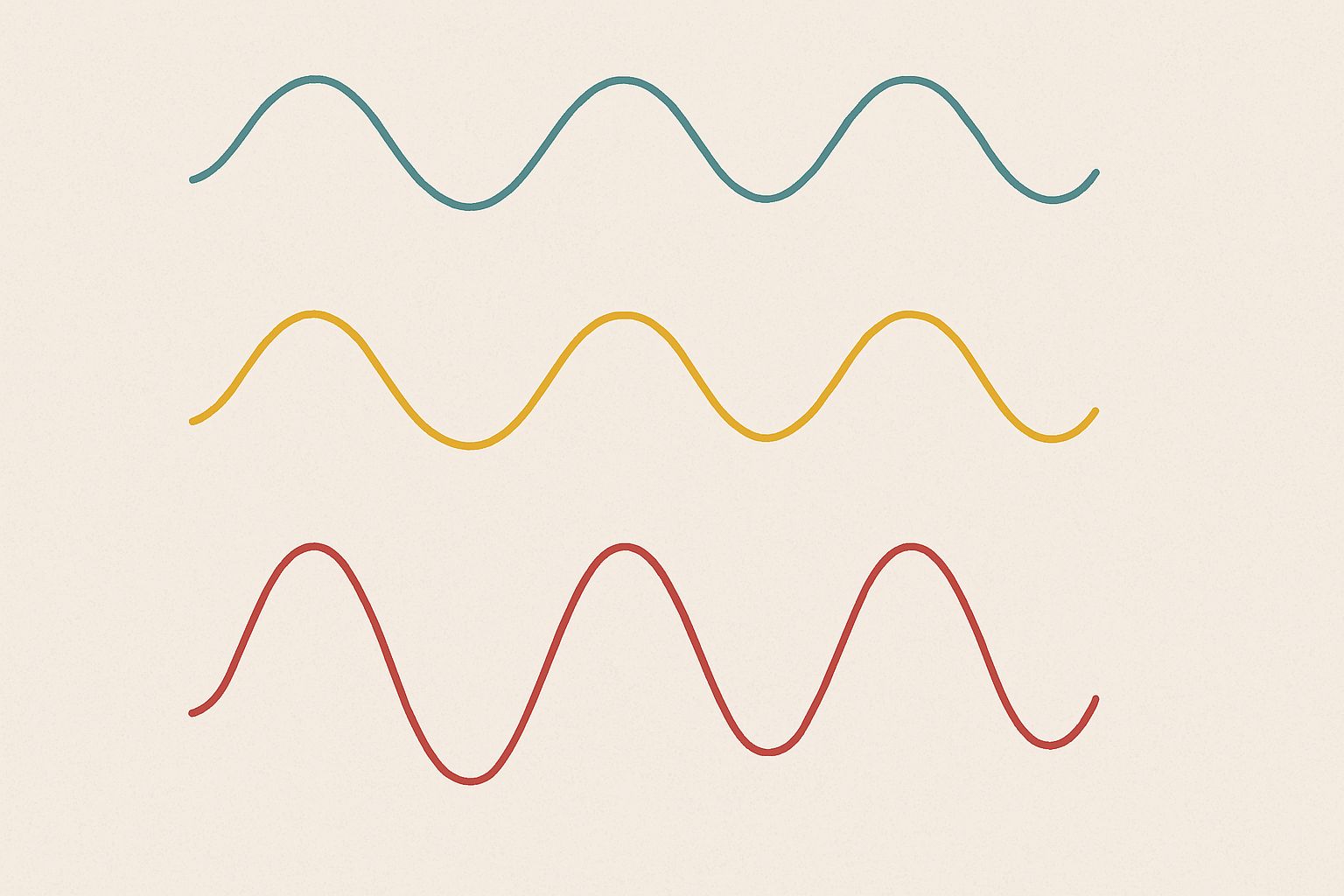

The same idea appears in mathematics. If a linear differential equation has two solutions, then any weighted mixture of those solutions is also valid. Linearity builds superposition directly into the mathematics. The figure below shows that the red curve which is sum of green and yellow is also a solution to the same wave equation!

Bringing everything together for quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is a mathematical model. It helps us understand phenomena at very small scales. But just as Earth is not really a point particle, the mathematical structure of quantum mechanics should not be mistaken for a literal picture of what an electron is doing.

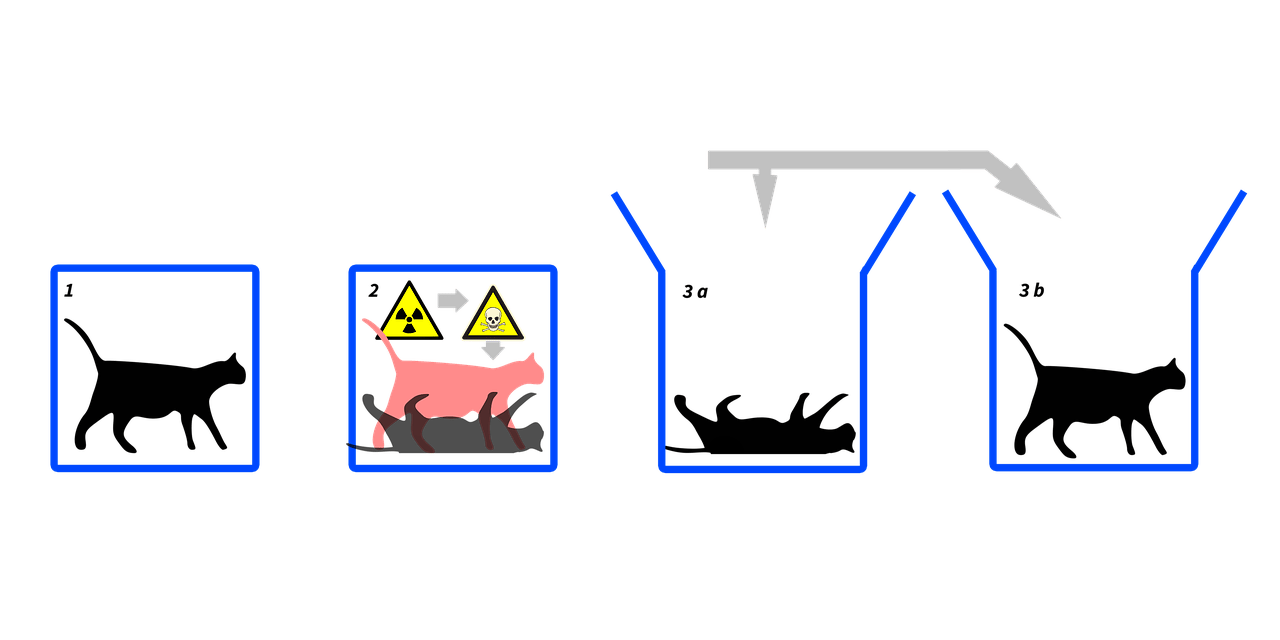

In earlier discussions we saw that electrons and light sometimes look like waves and sometimes like particles, depending on how we observe them. This naturally leads to the question. What are they when no one is observing them?

A naive answer is that they must still have a definite state. But this naive idea runs into trouble. Any measurement disturbs the system. So it is risky to assume it behaves the same way when there is no disturbance.

Just as the concept of motion depends on an observer's reference frame in classical physics, many properties in quantum mechanics, such as the position or spin of a particle, do not have definite values until they are measured by an experimental apparatus.

So how do we mathematically describe a system before a measurement?

We cannot represent it by a specific state as we just agreed we don’t know if a state would even exist before the measurement. Therefore a quantum system is mathematically described as being in a superposition of possible states. The act of measurement forces the system to "choose" a specific outcome, giving meaning to these properties in the context of that particular interaction.

Here linearity plays a central role. The core equation of quantum mechanics is linear. This means the possible mathematical descriptions combine through superposition. Yet what is being superposed is not a physical position or a physical wave. It is a probability amplitude. Only when we take the square of its magnitude do we get actual probabilities for outcomes. The superposition is a combination of possible outcomes rather than a combination of physical states in the classical sense.

This brings us full circle. Asking where an electron is when no one is measuring it is like asking if it is heads or tails when the coin is still in air. The question may not be meaningful in the way it appears. Quantum mechanics responds carefully. The position is not defined before measurement. The mathematics supports this. Linearity gives superposition. Superposition gives probability amplitudes. Probabilities appear only when an observer interacts with the system.

Quantum mechanics may appear strange at first, but once we accept that motion requires an observer and once we understand that models are not identical to reality, the superposition principle becomes natural rather than mysterious. It reveals a world that behaves differently from our everyday expectations, yet follows a clear and beautiful logic of its own.

In this sense, quantum mechanics challenges our classical intuition about an objective reality, highlighting that the values of certain physical properties may be undefined or indeterminate until measured.

Some important details:

Some of you have mentioned issues with emails not displaying correctly or figures not loading. If that happens, you can always click “Read online” in the top-right corner of the email to view the post in your browser. You can also visit the homepage https://qubit-and-neuron.beehiiv.com/ at anytime to see the latest updates.

Thank you all for your feedback and for letting me know about these issues. Please contact at: [email protected]