In our earlier discussion on quantum mechanics, we explored the strange idea that nature might be fundamentally random like “the ghost in the atom” (read here). Today, we turn to another deep and long-standing mystery at the heart of quantum physics: the true nature of light.

The Classical Picture: Light as Rays

For centuries, scientists studied light through the lens of geometry. Simple phenomena like reflection and refraction could be neatly explained by treating light as a collection of straight lines, or rays.

If a beam of light hits a mirror, it bounces off at an equal angle — a rule so straightforward that it became the foundation of ray optics. For a long time, this model seemed sufficient. It described how light travels, bends, and reflects with remarkable precision.

The Puzzle: The Double-Slit Experiment

But as experiments became more sophisticated, cracks began to appear in the ray model. The most famous challenge came from the double-slit experiment — an experiment so simple in design, yet so profound in its implications.

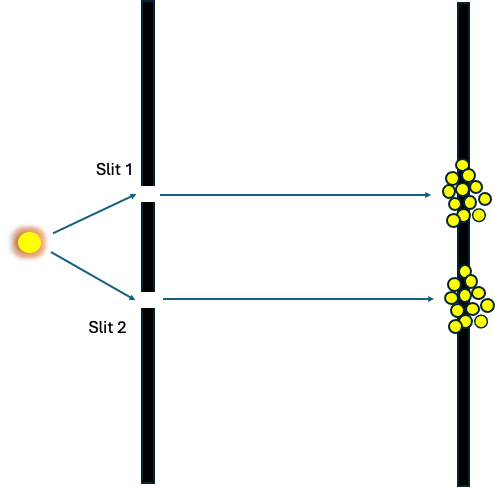

Imagine shining light through two narrow slits and observing what appears on a screen behind them. If light consisted of tiny particles, we’d expect two bright spots — one behind each slit. As shown in the figure below.

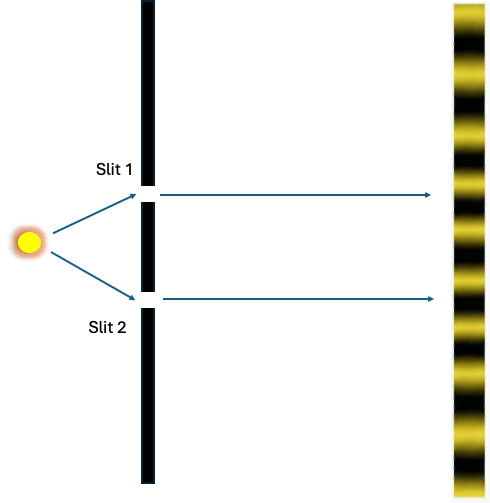

Instead, what emerges is a pattern of alternating bright and dark fringes — an interference pattern, where light waves combine and cancel each other.

The appearance of alternating bright and dark fringes was astonishing — almost beyond comprehension. How could adding more light ever produce darkness? This was something no one could explain if light were simply made of rays.

But the pattern looked familiar. When you drop a stone into still water, circular ripples spread outward and overlap. Where the peaks of two ripples meet, the water rises higher; where a peak meets a trough, they cancel each other and the surface flattens. Perhaps light behaves the same way — the bright regions appear where waves reinforce one another, and the dark regions where they cancel out completely.This meant that light plus light could produce darkness — something entirely impossible to explain if light is considered as a ray.

This experiment forced scientists to rethink their assumptions. Maybe light wasn’t a stream of rays or particles at all — maybe it was a wave.

Light as a Wave: A New Perspective

Once the wave picture took hold, many other puzzling phenomena suddenly made sense. The beautiful colors in soap bubbles, the shimmering patterns of oil on water, even the iridescent feathers of a peacock — all arise from interference of light waves.

Sound waves behave similarly. Two sound waves can overlap and cancel each other out — a principle behind noise-cancelling headphones. The wave model of light beautifully unified these effects and became the dominant theory for nearly a century.

The Twist

But nature had another surprise in store. When light shines on a metal surface, it can eject electrons — but only if the light’s frequency is high enough. Making the light brighter doesn’t help if its frequency is too low, while even a faint beam of high-frequency light can knock electrons out instantly. This observation made no sense if light were a continuous wave that simply poured energy onto the surface.

Einstein resolved the mystery by proposing that light consists of discrete packets of energy called photons, each carrying an amount of energy proportional to its frequency. If a photon has a high frequency, it carries more energy and can therefore knock an electron out of the metal surface. This revolutionary idea not only explained the photoelectric effect but also firmly established light’s particle-like behavior.

Yet, the double-slit experiment told a very different story. There, light showed clear signs of interference — a property of waves, not particles.

How could light be both?

Beyond Either/Or: Rethinking the Question

The central question — “Is light a wave or a particle?” — became one of the most famous paradoxes in physics. But perhaps the problem lies not in light, but in the question itself.

Consider asking: “Is water a liquid, a solid, or a gas?” The sensible answer is: it depends on the conditions. At room temperature, water is liquid; freeze it, and it becomes ice; heat it, and it becomes vapor. Asking what water “truly is” without specifying the conditions simply isn’t meaningful.

In much the same way, asking whether light is “really” a wave or “really” a particle misses the point.

Physics doesn’t reveal what light is in some ultimate sense — it tells us how light behaves under certain conditions.

Conclusion

What we’ve learned through quantum mechanics is that physics builds models, not metaphysical truths.

These models — mathematical frameworks describing how systems behave — allow us to make predictions. Depending on the setup, light exhibits wave-like or particle-like behavior. Both models are valid in their respective domains, and neither fully captures what light is beyond observation.

So it’s inaccurate to say “light is both a wave and a particle.”

A better statement is:

Light is neither a wave nor a particle. It behaves in ways that can be modeled as either, depending on the conditions.

Perhaps, someday, a deeper theory will unify all aspects of light into one coherent picture. But for now, quantum physics gives us a humbling truth: nature is not obligated to fit into the categories our minds find convenient.